YouTube ist für die einen Unterhaltungsmedium und für andere Einnahmequelle. Als Anfang des Jahres einem Studio aufgrund mehrerer Copyright-Beschwerden von YouTube die Einnahmen gestrichen wurden, wendete es sich an die Öffentlichkeit. Der Fall zeigt, wie problematisch der Umgang mit urheberrechtlich geschützten Inhalten auf YouTube ist und wie dessen Regeln ausgenutzt werden können. Für Farzaneh Badiei und Jonas Kaiser ist dies aber vor allem ein Versagen des Dispute Resolution Systems.

When a CEO publicly states that the company is „listening“ you know something’s up. So when YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki was forced to tweet these very words this came as a result to a week-long shitstorm which formed under the hashtags #wtfu (Where’s the Fair Use?) and #ProtectYouTubers. At the heart of this public outrage is YouTube’s implementation of the fair use doctrine (or perceived lack of) and how this system is being abused. The doctrine allows, in short, the public use of copyrighted material „for purposes of commentary and criticism„. Even though the distinction between fair use and copyright infringement has always been problematic this was radicalized through the Internet. Especially on a platform like YouTube where users upload everything from illegal TV series episodes, lectures on copyright laws or dancing to a song from the radio, the lines between fair use and copyright violation can get fuzzy pretty quickly. Especially so since some YouTubers nowadays make a living with videos that are heavily based around the usage of copyrighted material (e.g. playing video games or criticizing movies). To counter the ensuing problems YouTube implemented a system which automatically checks for copyrighted material and since this system is obviously not perfect gives copyright owners the additional opportunity to manually claim the violation of their copyright. The latter, however, has often times been abused, for example, to silence criticism or to profit from the video’s monetization. So when ChannelAwesome, a prominent YouTube studio, recently came out and described their problems with numerous copyright claims that lead to 23 days without income several prominent YouTubers joined them and shared their own stories. In these, they all echoed the same troubles with copyright claims or DMCA takedowns (based on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act) and the possibility of getting their channel suspended which for most is their source of income, too. They do, however, also emphasize that their problem lies primarily not with YouTube per se but rather the dispute resolution system in place.

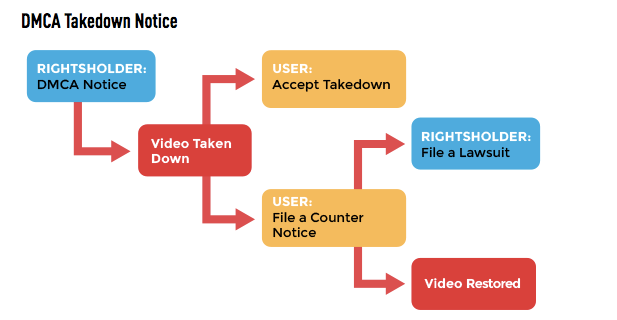

Based on ChannelAwsome’s experience, the current system of YouTube copyright claim handling (DMCA) breaches many of the normative criteria of justice in dispute management. Information about where to file the dispute is not accessible, rules change arbitrarily and without prior notice (affecting predictability), there are no time limits for providing an answer or it’s not followed and the accessibility of the copyright counterclaim is hampered by faulty counterclaim webforms. Even more problematic, the dispute management platform is not consistent (different users get different forms) and there is a word limit for DMCA – this obviously hampers representation and participation and can be considered unfair. The graph below, taken from Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) website illustrates the DMCA process:

It indeed seems as if YouTube is either not managing the disputes – or chooses to not get involved! But why hasn’t anyone at YouTube addressed this issue before? They have even gone so far as to offer legal support to videos that they believe represent clear fair uses which have been subject to DMCA takedowns, but do not get involved by providing a dispute resolution mechanism themselves. The answer might rest in the law itself. YouTube resolution system mirrors the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act (1996), Code 512 (g). Legally, copyright disputes on such platforms should be resolved by a court of law. As stipulated in g(3)(D) of DMCA,

Legal deterrents aside, YouTube might not want to manage the disputes as lawyers do not favor Dispute Management Systems. There are liabilities involved with such systems. They might have to adhere to a minimum standard of due process otherwise they can be sued. Even if their resolution is legally non-binding, they can still be taken to court. And they might be prone to class action lawsuits. Although in The Football Association Premier League Limited et al v. Youtube, Inc. et al court denied the certification of class action against YouTube in copyrights issues, challenging the dispute management system might not be denied.

Maintaining a dispute management system incurres a lot of costs and transaction costs on the provider. Does the benefit of providing a dispute management mechanism for YouTube outweigh its cost? It might not (for now). YouTube does not refer the disputes to be resolved by dispute management services, in other words simply outsource the provision of dispute resolution to some dispute resolution provider. This might be because of the liability issues that might arise from Code 512(g)(3)(D). Otherwise, referral of the disputes between the users of a platform in an copyright issues takes place. For example, eBay refers to the parties’ disputes about Feedback and Review system to Net neutral, an ODR provider.

What’s even more problematic: Competition does not help with incentivizing YouTube to provide dispute management either. YouTube has a dominant position in the online video market, so neither YouTubers nor customers can just leave the platform if they don’t like its copyright policy. Legally, YouTube is immune from being held liable for the content the users post on the platform. The DMCA obliges YouTube to have a takedown and notice process but it does not oblige YouTube to resolve the copyright dispute between the claimant and the defendant and refers the parties to court.

Overall, legally and economically YouTube does not have enough incentives to provide a system that resolves copyright disputes. The current law might even deter it from providing a dispute resolution mechanism let alone adhering to procedural justice. And the main question is: Are American courts suitable and accessible venues for taking global online copyright disputes? However, we have seen before that shitstorms and the publicity they usually bring may force companies to cave in. It remains to be seen though if this storm will bring YouTube to overthink their dispute resolution practices or if the issues will remain and the storm turned out to be in the teacup after all.